- Home

- Learn

- Severe Weather - Weather Information Portal

Severe Weather - Weather Information Portal

Forecasting severe weather poses a huge challenge to meteorologists all around the world

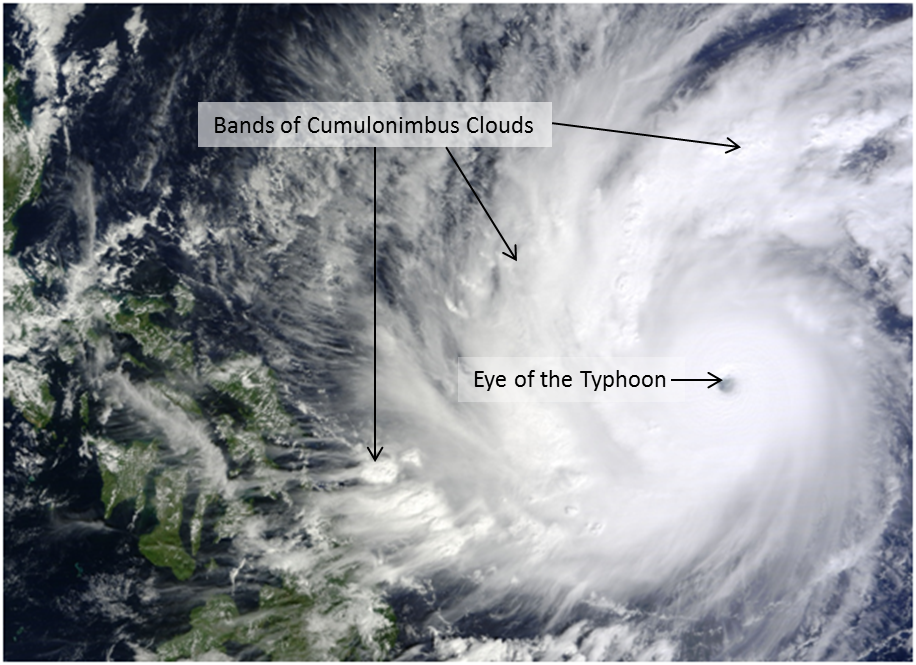

Tropical cyclones are one of the most dangerous natural hazards. A cyclone is fundamentally a huge rotating storm centred around an area of low pressure with strong winds blowing around it. The centre of the low pressure area is called the eye of the storm, where the weather is calm with clear skies.

Formation of tropical cyclones

Various trigger mechanisms are required to transform storms into less frequent tropical cyclones. The key factors are a source of very warm, moist air derived from tropical oceans with surface temperatures greater than 26 degrees Celsius, and sufficient spin or Coriolis force from the rotating earth.

As the warm ocean heats the air above it, a current of very warm moist air rises quickly, creating a centre of intense low pressure at the surface. Winds rush in towards this low pressure and the inward spiraling winds whirl upwards, releasing heat and moisture when descending. The earth’s rotation causes the rising column to spin, taking on the form of a cylinder whirling around an eye of relatively still, cloud-free air. The rising air cools and produces towering cumulus and cumulonimbus clouds.

A tropical cyclone develops in stages, beginning as a tropical depression with sustained wind speeds at a maximum of 63 km/h (34 knots), growing into a tropical storm with wind speeds greater than 63 km/h (34 knots) but less than 119 km/h (64 knots), and finally developing into a cyclone when wind speeds exceed 119 km per hour (64 knots).

Global map showing the tracks followed by tropical cyclones in areas most affected by Tropical Cyclones. The tracks are curved because of “steering” by high level winds (Image credit: NOAA)

Global map showing the tracks followed by tropical cyclones in areas most affected by Tropical Cyclones. The tracks are curved because of “steering” by high level winds (Image credit: NOAA)

Typically lasting several days, cyclones gradually dissipate as they move over cooler waters or hit land. If they stay in favourable warm seas, they can last for weeks. In the northwest Pacific and South China Sea, they can form throughout the year but are more common from May to November.

Typhoon Hagupit (most intense storm that affected the Philippines in 2014) with a well-formed eye at its core and bands of cumulonimbus clouds extending thousands of kilometres (Image credit: NASA)

Typhoon Hagupit (most intense storm that affected the Philippines in 2014) with a well-formed eye at its core and bands of cumulonimbus clouds extending thousands of kilometres (Image credit: NASA)

Generally tropical cyclones occur between 5 and 30 degrees latitude, and do not form in the equatorial regions because the Coriolis effect is negligible near the equator. However the rare occurrence of two colliding systems can lead to cyclone development. In December 2001, typhoon Vamei formed when strong winds from a monsoon surge interacted with an intense circulation system in the South China Sea. Typhoon Vamei came within 50 km northeast of Singapore and brought windy and wet conditions to Singapore.

Identification of Tropical Cyclones

Tropical cyclones are called typhoons in the northwest Pacific Ocean, hurricanes in the Atlantic Ocean and cyclones in the Indian Ocean. Each tropical cyclone is named for quick identification in warning messages. The names of cyclones in the northwest Pacific and South China Sea are contributed by the countries surrounding the region, based on their cultural familiarity. The latest list of names is found here.

Storm surge

The intense low pressure at the centre of a tropical cyclone can combine with the effect of strong winds to raise the ocean surface by several metres. This effect is called a storm surge, and can cause serious flood damage to low-lying coastlines.

There is no universally accepted definition of drought. Drought is defined and measured, in various ways by different users, for different purposes. It is broadly perceived in three different ways:

- Meteorological drought: When actual rainfall over an area is significantly less than the climatological mean.

- Hydrological drought: When there is marked depletion of surface water causing very low stream flow and drying of reservoirs and rivers.

- Agricultural drought: When inadequate soil moisture produces acute crop stress and affects productivity.

The meteorological definition of drought focuses on the degree of dryness and duration of the dry period, compared to the historical long-term average for the specific region.

Drought is an inevitable part of the normal variability of climate. Perhaps the most widely known cause of larger scale droughts is the recurring climatic anomaly called the El Nino phenomenon. Many of the widespread and severe droughts affecting different parts of the world were a direct consequence of El Nino events. In 1997, the occurrence of one of the strongest El Nino events led to the lowest annual rainfall in Singapore (1118.9 mm) since rainfall records started in 1869.

A heatwave is an extended period of unusually hot weather, which usually lasts from a few days to several weeks. There is no universal definition for heatwave as weather conditions vary across different regions of the world. What would constitute a heatwave in London might just be a bit warm in Kuala Lumpur and quite normal in New Delhi. As such, each country has its own definition of a heatwave based on its history of extreme temperatures and other climatic conditions.

A heatwave has its greatest impact on people usually after several days of very warm temperatures. The impact is heightened if the humidity is also high. When a heatwave reaches extreme levels, it can cause heat strokes and even deaths among the more vulnerable members of the population.

In Singapore, a heatwave occurs when the average daily maximum temperature is at least 35°C for three consecutive days, and the average daily mean temperature throughout the period is at least 29°C.

Haze consists of dust, smoke, and other dry particles that are suspended in the air and obscure visibility. Haze can form under light wind conditions and a stable atmosphere, when fine particles aggregate and are suspended in the air; this is common in the early morning but disperses during the day as winds strengthen. Haze is sometimes confused with mist and fog, which also reduce visibility but have no impact to the environment.

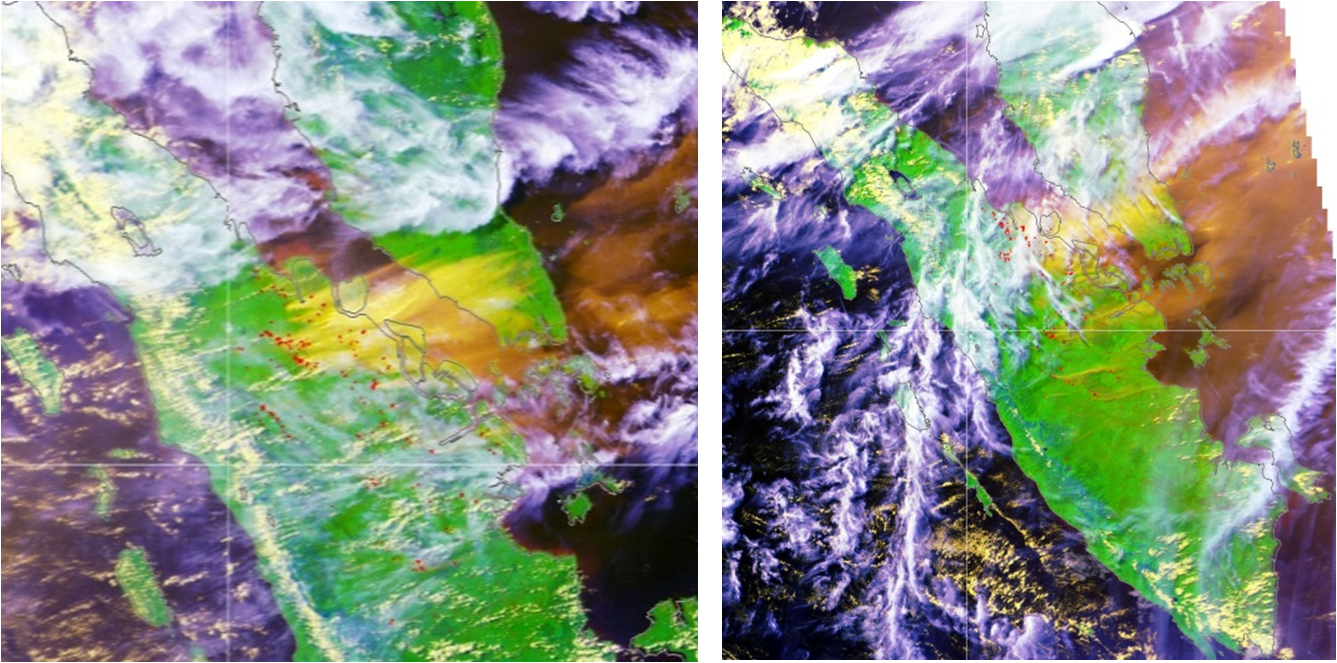

Transboundary haze, on the other hand, is a greater cause for concern, as it is not only environmentally destructive but also poses severe risks to human health and transportation. It originates from burning land and forest fires, particularly peat lands, in the region.

Singapore shrouded by transboundary smoke haze

Singapore shrouded by transboundary smoke haze

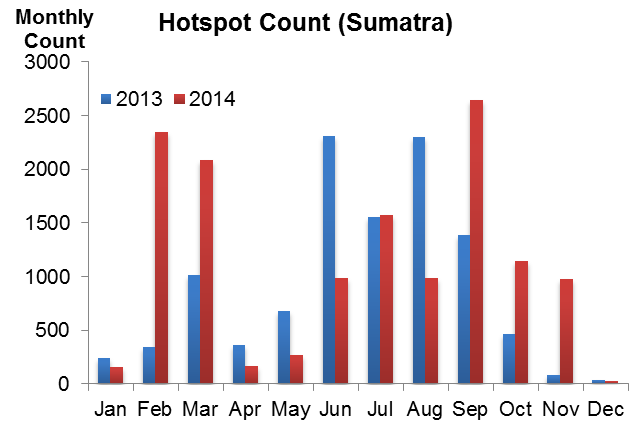

The occurrence of transboundary haze in the southern ASEAN region (comprising Singapore, Malaysia, Brunei, and Indonesia) is more common during the traditional dry season between June and early October. During extended periods of dry weather conditions, increased burning activities tend to occur in the fire-prone areas of the region. Smoke haze from fires is carried over by prevailing winds to other countries in the region. The severity of the smoke haze affecting an area or country downwind of the source depends on various factors including the proximity and extent of the fires, and the direction and strength of the prevailing winds.

Monthly hotspot count for Sumatra in 2013 and 2014.Hotspot activities usually peak in the traditional dry season from June to September. A prolonged dry spell in early 2014 also led to a spike in the number of hotspots

Monthly hotspot count for Sumatra in 2013 and 2014.Hotspot activities usually peak in the traditional dry season from June to September. A prolonged dry spell in early 2014 also led to a spike in the number of hotspots

Singapore has been affected by severe transboundary haze episodes, notably in 1994, 1997, 2006 and 2013. In June 2013 thick smoke haze from central Sumatra affected Singapore over a two-week period, carried over by unseasonal westerly winds. The “very unhealthy” 24-hour PSI reading of 246, registered on 22 June 2013, was the worst since 1994.

Satellite images (18 June (left) and 23 June (right)) of transboundary smoke haze affecting the region in June 2013

Satellite images (18 June (left) and 23 June (right)) of transboundary smoke haze affecting the region in June 2013

Weather creates hazards for ships and aircraft. At sea, wind waves and swell produced by storms are the major hazards. In the air, the main hazards are hailstones and microbursts, both of which are produced by intense thunderstorms. Thick fog is a hazard to sea and air operations as it can significantly reduce visibility, obscuring coastlines and airport runways.

Waves and Swell

The sea state at any location is usually a combination of wind wave and swell. Huge sea waves, usually associated with tropical cyclones and monsoon surges, pose a threat to the safety of mariners.

Wind waves are short waves generated by local winds. Just how big the waves are depends on the strength of the winds, how long they blow, and how far they blow over the sea (the “fetch”). The waves can rise to heights of over 15 metres in the vicinity of tropical cyclones in the open sea.

Wind wave (left) and Swell wave (right). Wind waves are surface winds resulting from winds blowing over the ocean’s surface. Swell waves are a series of wind–generated waves not by local winds at that time but by winds from distant weather systems blown for a duration of time and distance over the ocean (Image credit:

Wind wave (left) and Swell wave (right). Wind waves are surface winds resulting from winds blowing over the ocean’s surface. Swell waves are a series of wind–generated waves not by local winds at that time but by winds from distant weather systems blown for a duration of time and distance over the ocean (Image credit:

www.earthsci.org/index.html)

Swells are longer waves that propagate away from the point where they originated. Swells, when generated by tropical cyclones, can propagate out of their generation zones and travel very long distances across the ocean. They have very low correlation to the local winds. Swells propagate much faster than the tropical cyclone itself, reaching the coastal areas way ahead of the tropical cyclone making landfall. When swells enter shallow waters, their heights increase and pose a hazard to people staying along coastal areas.

Fog

Fog consists of numerous tiny water droplets suspended in the air — this is what obscures our vision. In the presence of fog, the visibility is below 1 km. It is known as mist when visibility is between 1 and 5 km. Under light wind, humid and clear sky conditions, moisture near the ground can often condense near the ground to form fog or mist, especially at dawn or dusk. Fog and mist are actually ground-level stratus clouds.

Fog rarely occurs in Singapore. However mist is not uncommon, especially during inter-monsoon periods when winds are generally light, and is commonly found in forested areas on cool nights and in the early morning.