EI Niño/La Niña Status

Updated on 7 July 2025

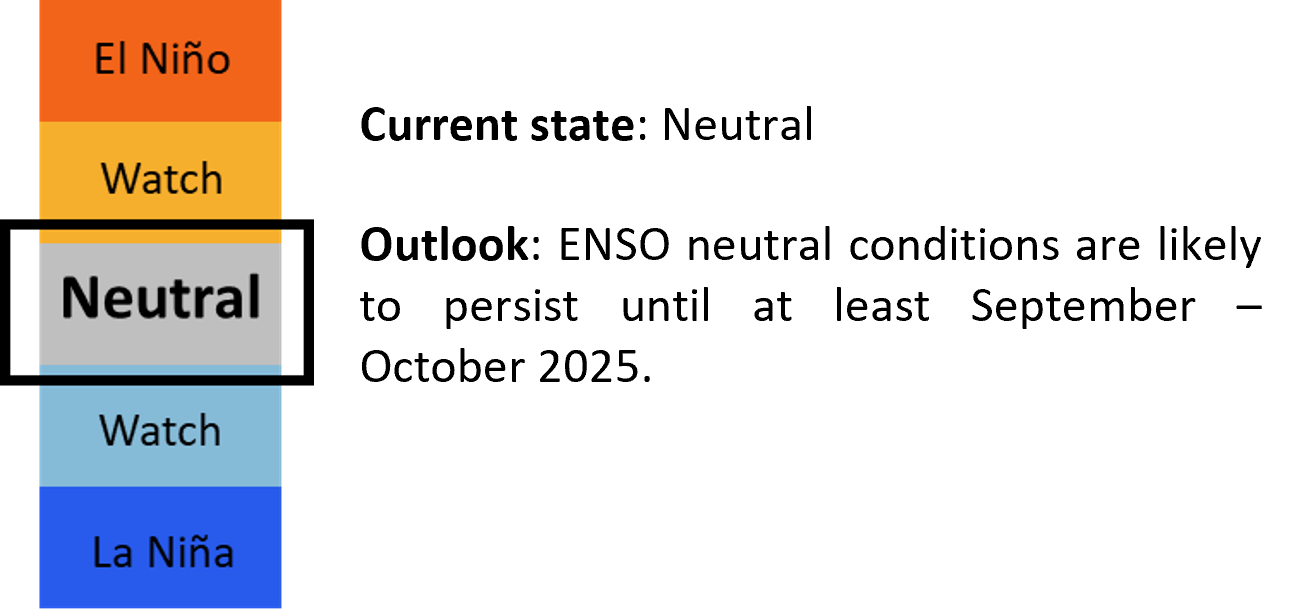

The El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) monitoring system state is “Neutral”. The Nino3.4 index is within the ENSO-neutral range, with key atmospheric indicators (cloudiness and trade winds in the central Pacific) also showing ENSO-neutral conditions. The Nino3.4 index was -0.36°C for May 2025 and -0.29°C for the March – May 2025 three-month average.

Models predict ENSO-neutral conditions during July – August 2025. Overall, models predict ENSO-neutral conditions are most likely to persist until at least October 2025, although some models indicate possible La Niña development from September.

Short note on the Indian Ocean Dipole: The Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) is neutral, with models predicting neutral conditions to persist in July and then either neutral conditions to persist or a negative IOD to develop during August – September 2025.

Further Information on ENSO

ENSO conditions are monitored by analysing Pacific sea surface temperatures (SSTs), low level winds, cloudiness (using outgoing longwave radiation), and sub-surface temperatures. Special attention is given to SSTs, as they are one of the key indicators used to monitor ENSO. Here, three different datasets are used: HadISST, ERSSTv5, and COBE datasets. As globally, SSTs have gradually warmed over the last century under the influence of climate change, the SST values over the Nino3.4 will increasingly be magnified with time, and hence appear warmer than they should be. Therefore, this background trend is removed from the SST datasets (Turkington, Timbal, & Rahmat, 2018), before calculating SST anomalies using the climatology period 1976-2014. So far, there has been no noticeable background trend in the low-level winds or cloudiness.

El Niño (La Niña) conditions are associated with warmer (colder) SSTs in the central and eastern Pacific. The threshold for an El Niño (La Niña) in the Nino3.4 region is above 0.65°C (below -0.65°C). El Niño (La Niña) conditions also correspond to an increase (decrease) in cloudiness around or to the east of the international dateline (180°), with a decrease (increase) in cloudiness in the west. There is also a decrease (increase) in the trade winds in the eastern Pacific. Sub-surface temperatures in the eastern Pacific should also be warmer (colder) than average, to sustain the El Niño (La Niña) conditions.

For ENSO outlooks, information from the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) and international climate centres are assessed. The centres include the Climate Prediction Center (CPC) USA, the Bureau of Meteorology (BoM) Australia, as well as information from the International Research Institute for Climate and Society (IRI) which consolidates model outputs from other centres around the world. Each centre uses different criteria, including different SST thresholds. Therefore, variations between centres on the current ENSO state should be expected, especially when conditions are borderline.

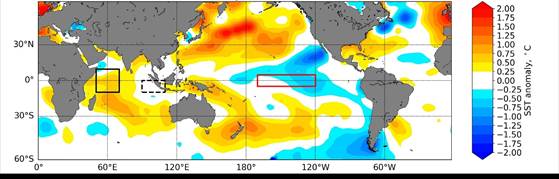

The sea surface temperatures (SSTs) over the tropical Pacific in May 2025 were above average in the west, below to near average elsewhere (Figure 1). The coolest (negative) anomalies were around the eastern half of the Nino3.4 region (red box). Across the Indian Ocean, the western portion was above average while the eastern tropical portion was near average (solid black box and dashed black box, respectively), although overall still indicating neutral IOD conditions.

Figure 1: Detrended SST anomalies for May 2025 with respect to 1976-2014 climatology using ERSST v5 data. Red (blue) shades show regions of relative warming (cooling). The tropical Pacific Ocean Nino3.4 Region is outlined in red. The Indian Ocean Dipole index is the difference between average SST anomalies over the western Indian Ocean (black solid box) and the eastern Indian Ocean (black dotted box).

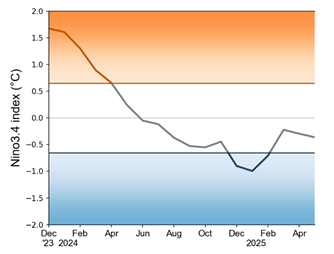

Looking at the Nino3.4 index in Figure 2, in early 2024 there was a gradual shift from El Niño to ENSO neutral, with the Nino3.4 index within the neutral range by May 2024. Between May and November 2024, the 1-month Nino3.4 index was within the neutral range, with a gradual cooling of the index and approaching the La Niña threshold. The index passed the La Niña threshold in December 2024 and returning to ENSO neutral in March 2025. Since then, the index has been negative, but within the ENSO neutral range.

Figure 2: The Nino3.4 index using the 1-month SST anomalies. Warm anomalies (≥ +0.65; brown) correspond to El Niño conditions while cold anomalies (≤ -0.65; blue) correspond to La Niña conditions; otherwise neutral (> -0.65 and < +0.65; grey).

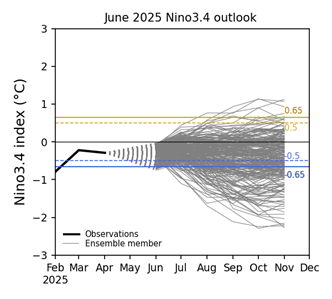

Model outlooks from Copernicus C3S (Figure 3), based on the Nino3.4 SST index, show that models predict ENSO neutral conditions in July – August 2025. For September – November 2025, models predict either ENSO neutral conditions or La Niña conditions, although the chance of ENSO neutral conditions is higher than for La Niña.

Figure 3: Forecasts of Nino3.4 index’s strength until November 2025 from various seasonal prediction models from international climate centres (grey lines). The solid blue and yellow lines note the La Niña and El Niño thresholds used by MSS, while the dotted lines note the thresholds used by some other international centres.

Historical ENSO Variability

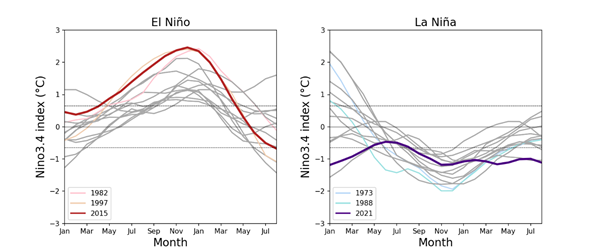

To classify a historical El Niño event, the 3-month average Nino3.4 value must be above 0.65°C for 5 or more consecutive months. For La Niña events, the threshold is -0.65°C. Otherwise it is considered neutral. ENSO events with a peak value above 1.5°C (El Niño) or below -1.5°C (La Niña) are considered strong. Otherwise, the events are considered weak to moderate in strength. The following figure (Figure 4) shows the development of the Nino3.4 index for the most recent El Niño and La Niña events in comparison to other El Niño/La Niña events.

Figure 4: Three-month Nino3.4 index development and retreat of different El Niño (left)/La Niña (right) events since the 1960s. Recent El Niño and La Niña events are in red and purple, respectively.

Impact of El Niño/La Niña on Singapore

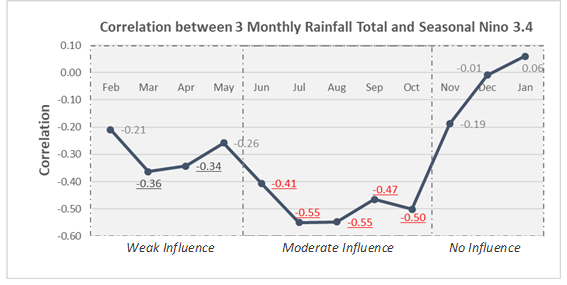

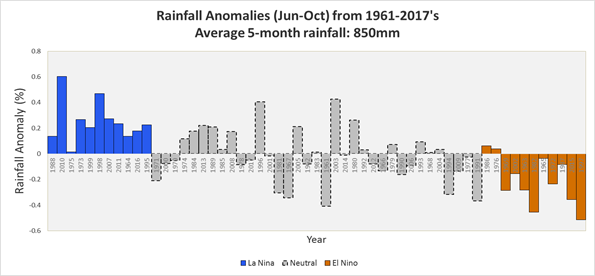

During the Southwest Monsoon months from June to September the correlation of ENSO with rainfall over Singapore is strong (Figure 5), i.e. if an El Niño or La Niña conditions are present, the rainfall patterns are likely to be influenced, particularly by a moderate or strong event. When there neither El Niño nor La Niña conditions are present (i.e. ENSO-neutral), there is a large variability in rainfall (Figure 6).

Figure 5: Correlation between total seasonal rainfall (averaged over 5 Singapore stations) and seasonal Nino3.4 index from 1961-2017 centred on the month indicated (e.g., for June’s value it corresponds to season May-June-July). The statistically significant correlations at the 95% level are underlined, at 99% level in red.

Figure 6: Singapore rainfall anomalies for June – October (as a percentage of departure from long-term rainfall average) arranged in the order from strong La Niña (left) to strong El Niño (right). Brown bars denote El Niño years’ anomalies, blue bars denote La Niña years’ anomalies, and grey bars denote ENSO neutral years’ anomalies.

References

Turkington, T., Timbal, B., & Rahmat, R. (2018). The impact of global warming on sea surface temperature based El Nino Southern Oscillation monitoring indices. International Journal of Climatology, 39(2).